Heraldic Frocks

The purpose of this article is to discuss heraldic dresses for women, with a view to being of use to medieval re-enactors who wish to create these types of garments. Even though depictions of such dresses appear on numerous period sources: armorial rolls, funereal monuments, brass effigies/inscriptions and illuminated manuscripts, it must be stated at this point that there appears to be little concrete evidence to support the concept of gowns displaying heraldry on an entire garment in a fashionable context. Currently, the belief is that these representations are primarily for symbolic identification, as many noble personages were instantly recognisable to the populace solely by their heraldry in what was largely an illiterate age. The use of heraldry in these art forms would have left no doubt as to the identity of the persons being portrayed, which explains its inclusion on items seen by people who may not have had the benefit of knowing the person depicted firsthand.

Figure 1 (Cantor)

Le Roman de la Poire, Paris c. 1260-70.

Bibliotheque Nationale Paris,

French Manuscript - MS fr 1584,fol4IV.

Whilst the full heraldic adornment on fashionable garments seems unlikely, there is one notable exception - royal ceremonial garments. On important state occasions, it appears possible that royal and women of high rank could have been clothed in the elaborately emblazoned ceremonial gowns, which appear in so many disparate period art forms. Along with these regal heraldic gowns, it also seems possible that heraldic mantles and cloaks might have been made for the same official state purposes.

Gowns and cloaks bearing sophisticated heraldic display of this nature confer rank, wealth and status, which were necessary commodities in the medieval royal court. While it seems likely that queens and royal princesses would have dressed in gowns depicting the arms of their countries, likewise for royalty or their officers to be garbed in heraldic mantles and cloaks for state occasions, it is implausible that minor nobles would have had similar heraldic garments made bearing their own personal arms, as they would have less occasion requiring ceremonial dresses of this nature. (Netherton)

Heraldic Clothing For Men

Heraldic clothing for men on the other hand has far more to substantiate its existence. Originating from a necessity to identify friend from foe on the chaotic medieval battlefield, heraldic tabards and surcotes for fighting men allow easy identification even in absence of shields. A mounted knight or fighter with sword in one hand, and reins in the other would still be identifiable by his clothing. Herald’s tabards, and soldier’s uniforms were worn to show allegiance to a particular Lord, and often livery of this type provided protection to their wearers.

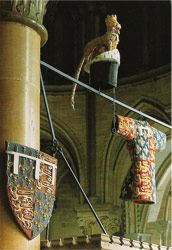

A few extant examples of jupons and surcotes support the use of heraldic insignia on the clothing of fighting men. A most famous extant jupon can be found amongst the accoutrements of Edward, the Black Prince, on display at Canterbury Cathedral. We see the same garment represented by various artists in different contexts - the brass monument on his tomb at Canterbury Cathedral c. 1380 (Figure 2), an engraving by an unknown artist of 1356 (Figure 3), and an illuminated manuscript of 1386-1399 (Figure 4), and can see how these artists treated their subject.

Figure 2 (Bartlett)

Tomb monument to Edward the Black Prince (Canterbury Cathedral, c.1380)

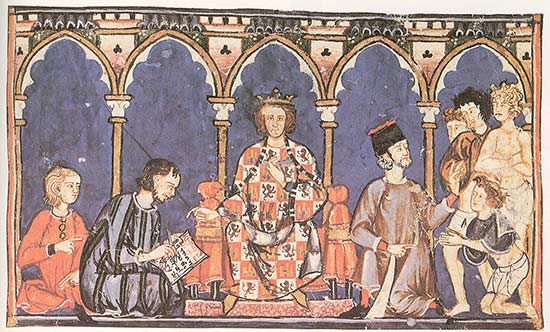

A fantastic example of men’s secular, and non-combatant heraldic clothing can be found in the manuscripts of the Libro des Jeugas from the 13th century, (Spanish Monastery of the Esconial). Here, Alfonso X, King of Spain (1252-1284), is depicted wearing what appears to be a tunic and a cloak bearing the arms of the royal house of Leon and Castille. (Figure 7).

Figure7 (Carretero)

Alfonso X, King of Spain (1252-1284)

Manuscript from Libro des Jeugas, Spanish Monastery of the Esconial.

‘Some of the finest embroidery and weaving went into creating such garments. Clothes like these denote rank and were an integral part of the ordering of medieval society.’

(Hallam, pg. 186)

Initially this statement seemed to be an undocumented generalization until extant garments supported this view. The half silk woven fabric used in these items is similar to that depicted in the manuscript - which was possibly simplified by the artist for ease of representation in miniature.

Figure (8) and (9)

Burial alijuba of Don Fernando de la Cerda (tunic) circa1270

Monasterio de Santa Maria de Huelgas, Burgos Spain and detail of fabric

This ‘alijuba’ (tunic, Figure 8) of woven half silk fabric (Figure 9), is a product of the Mudejar workshop in Spain, and was the burial outfit of Don Fernando de la Cerda, crown prince of Castile, who was buried in 1275. Don Fernando’s alijuba, along with a ‘pellote’ (sideless surcote - see Figure 29 below) and a mantle of the same fabric are in the collections of the Museo de Telas Medievales (Monasterio de Santa Maria de Huelgas, in Burgos, Spain).

Heraldic Clothing For Women

The body of academic work available on the topic of heraldic garments for women is often ambiguous, leaving more questions unanswered than satisfied. Yet many of us, enamoured of these spectacular heraldic gowns, still wish to research their origins with a view to creating them for re-enactment purposes. This leads us to a discussion of the types and styles of dresses found in various sources.

These sources include, but are not limited to:

- funereal monuments

- brass effigies and inscriptions

- illuminated manuscripts

- extant garments and textiles

- armorial rolls

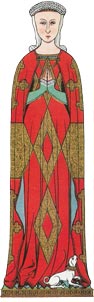

Funeral effigies and monumental brasses are a good source for imagery of women’s heraldic dresses. Many of these appear emblazoned with the arms of the deceased (her husband and father) as an effective marker of their identity, nobility and social status. Even relatively minor nobles are quite commonly depicted in heraldic dress in brass funereal monuments.

Illuminated manuscripts often designed to commemorate important events, such as coronations, presentations at court, wedding ceremonies and state processions. In these manuscript illustrations, the heraldic dresses, tunics and cloaks effectively denote royal personages - so that the viewer can instantly identify the people in the picture. Minor nobles attired in heraldic dress appear less frequently than royalty in these images. These miniatures are found in:

- English manuscripts of the 12th -14th centuries;

- French manuscripts of the 13th - 16th centuries;

- Spanish manuscripts also of the 13th century

- and no doubt in other periods and cultures omitted here.

Armorial rolls such as the Baillol (1332), Forman (1563), and Seton (1591) Rolls all contain imagery of women in heraldic dresses. The foremost function of an Armorial Roll is to list and document heraldic devices in a ‘Roll of Arms, which allows identification of noble persons by their heraldry alone. They also serve as a method of publishing ownership of arms.

Representations of women in heraldic dresses can be found over many diverse periods and cultures in the various artistic disciplines mentioned above. The most frequently occurring dress styles appear to be:

- cotehardies (13th to 15th century)

- sideless surcotes (12th to 15th centuries);

- Tudor/Elizabethan style (16th century).

|  |  |

|---|---|---|

| Cotehardie | Sideless Surcote | Tudor/Elizabethan |

| Figure 11a (Evans) Luttrell Psalter English (1330-1335) British Library, London | Figure 11b (Voronova) Duke of Burgundy’s bride (1450) Osterreicheische Nationalbibliothek | Figure 11c (Cantor) Mary Queen of Scots and Dauphin of France Seton Armorial (1591) |

Cotehardies

Some of the most widely discussed examples of women’s heraldic gowns are the ones depicted in the Luttrell Psalter (Figure 12). The Luttrell Psalter is a secular manuscript commissioned by Sir Geoffrey Luttrell in the early 14th century. In it, there are over 300 illustrations, many of which depict medieval life on his lands in Lincolnshire. This particular image (Figure 12), shows Sir Geoffrey heading off to tournament. His equipage is covered in his heraldry (Azure, a bend and six swifts Or). His wife, Agnes Sutton, is wearing a gown showing the arms of Sir Geoffrey impaled with the arms Sutton in a full garment armorial display. That is, the arms of her husband are depicted on the right half of her dress, and the arms of her father on the left half of her dress.

Figure 12 (Evans)

Sir Geoffrey Luttrell being seen off to tournament by his wife (Agnes Sutton)

and daughter in law (Beatrice Scrope). Luttrell Psalter 1335-1340. English British Library

NB - Something bothersome about this particular image is the way in which the bend alternates direction to become a bend sinister -Bend on the shield, surcote and the dresses, Bend Sinister on the horse coverings and pennons and mini jousting shield. Why? While this article isn’t intended as a study of Heraldry, some analysis and discussion of heraldic information has been included because of the interesting social information it can impart.

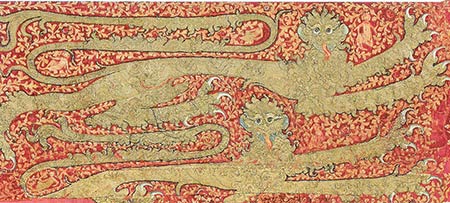

The heraldic horse covering shown above, with it’s diapered background, is reminiscent of a fragment of a horse covering, richly embroidered with the lions of England, believed to have belonged to Edward III (Figure 13). Few would doubt that Sir Geoffrey Luttrell might have bedecked his horse in this way for the tournament. This being the case, it seems remarkable that there would be large heraldic embellishments on such things as a nobleman’s horse, and not his wife!

Figure 13. (Staniland) Fragment of Edward III’s Heraldic Horsecloth c1348

More examples of cotehardies with full garment armorial display can be found amongst brass funereal monuments. Here we see many examples of heraldic dresses worn by women of minor noble families, and not just from the upper echelons of Royalty. Frequently depicted alongside these noble women are their husbands, often also in heraldic garments. We accept quite readily that these jupons and armorial tabards actually existed, but without extant examples, there is resistance to accepting these representations as definitive evidence for women’s heraldic dresses.

Figure 14

Lady Maude, Sir John and Lady Joan de Foxley, 1378 Monumental Brass Society Bray, Berkshire

One such example is that of Lady Matilde (mostly known as Maude) de Foxley, who is depicted wearing a heraldic cotehardie in a brass funereal monument of 1378. Maude de Foxley is the first wife of Sir John de Foxley . Barely discernible, on the right side of her dress, she bears the arms of Sir John de Foxley ‘Gules, two bars argent’. The arms on the left side of her dress ‘Sable, a lion rampant Or’ are those of her father, Sir John Brocas of Beaurepaire in Hampshire. (Figure 14)

Sir John de Foxley’s tomb effigy also depicts his second wife, Joan who appears in a much plainer dress. The last will and testament of Sir John de Foxley, a relatively minor noble, states that the brass for Lady Maude should be more elaborate to show the wealth and status she bought to the family.

These two images (Figures 15 and 16) are from an English brass monument of 1384. In it, Lady Harswyck is depicted in a dress that bears the arms of Harswyck - ‘Or a chief sable, indented of four points’ and Gestingthorpe, ‘Ermine a maunche gules’. These are the documented, historic arms of her husband and her father.

|  |

|---|---|

| Figure 15 (Houston) | Figure 16 (Coss) |

| Sir John and Lady Harswyck Artist’s Representation | Original Brass Monument South Acre, Norfolk 1384 |

According to Houston, these motifs were ‘probably embroidered’. However, she unfortunately does not offer any basis for this statement (Houston, pg110), and as such other methods of construction should not be discounted. This elaborate brass effigy honours the relatively minor noble family of Harswyck. Sophisticated commemorative monuments of this type serve to memorialise the deceased, but also to bolster the family’s status with a display of wealth, (a kind of posthumous bragging) therefore they can not be unequivocally regarded as evidentiary.

Figures 17 and 18

Margaret Ferrers, wife of Thomas de Beauchamp, 4th Earl of Warwick.

English brass monument 1406. St Mary’s Church Warwick.

Lady Margaret Ferrers, daughter of William Ferrers, 3rd Lord of Groby, (Figure 17) is depicted wearing both a heraldic cotehardie and a heraldic mantle. (A drawn version of this brass, Figure 18 has been included to for a clearer representation).

The likelihood of cloaks and mantles for ceremonial occasions is more likely than the use full garment heraldic dresses, so where does that leave us regards this dress? If mantles of this nature existed, should that not apply to the dress also, seeing that they are seen here represented in the same source? As this depiction is not of a particularly high ranking or royal woman, it seems more likely that this representation is iconographic rather than evidentiary.

Something I find fascinating in this image, is that Lady Margaret’s mantle bears the arms of Beauchamp (her husband), but her dress bears the arms of Ferrers (her family/father), making this an interesting juxtaposition of inherited and marital arms on two separate garments, rather than impaled on a single gown.

This image depicts two women in full garment heraldic cotehardies. The image of Anne, Dauphine D’Auvergne (Figure 19) and her attendant , la Dame de Nedouchel is credited to have come from a book published in 1867 called ‘Iconographie Generale et Methodique du Costume du IVe au XIXe Siecle (315-1815)’, by Raphael-Andre Jacquemin. (The General Iconography and Methods of Costume from 315-1815) (Houston Plate IV).

Unfortunately, in the original publication, Jacquemin doesn’t give any further details (not even a date!) as to where he has sourced this image, so it needs to be regarded with scepticism, and certainly not to be considered as evidentiary. I have included it, because Houston is a well known text but must be considered poorly documented. I am still trying to find the original document or brass that these dresses are drawn from. Though I anticipate that the source may have little resemblance to this drawing.

Figure 19 (Jacquemin)

Anne, Duaphine d’Auvergne, Comtesse du Foret

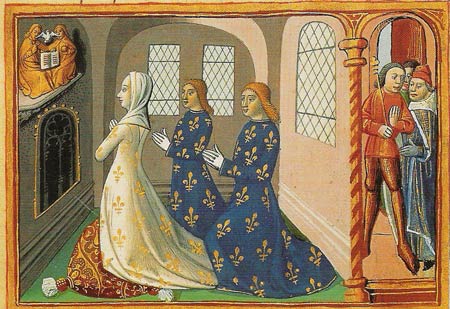

The image below (Figure 20) is the only example included here that depicts a cotehardie style dress with strewn charges rather than a full garment armorial display. The woman depicted in white, is not a particular person, but rather a personification of France as a nation. She is kneeling before and worshipping the Holy Trinity. This spiritual representation is an invented image, and not intended to be factual.

Figure 20 (Bartlett)

‘France’ worshiping the Trinity - French Manuscript late 15th C. Bibliotheque Nationale, Paris MS Fr5054 f35v

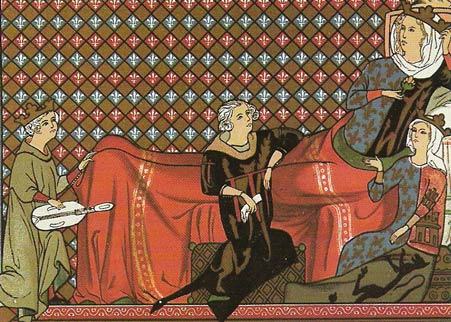

This image (Figure 21) shows Queen Blanche of Castille lounging in a spectacular marshalled heraldic gown. We have already briefly mentioned, and will discuss further below, the likelihood of royal women being dressed in heraldic ceremonial robes is substantial. However, this manuscript illustration does not depict Queen Blanche in any ceremonial capacity - in fact, it is quite the opposite. Therefore, while Queen Blanche could have owned a dress like this, in this image, it seems more likely that artist has included the dress as an identifier rather than a true representation.

Figure 21 (Cantor)

Queen Blanche of Castille with her attendants listening to a minstrel

(Miniature, French 13th C. Arsenal, Paris MSA5B.L)

Cotehardies - Design And Construction Considerations

Even though there is scant evidence to support period use of heraldic cotehardies, they have a very ‘medieval’ feel to the modern eye, Should you wish to pursue the creation of one of these dresses, there are a number of period design forms to follow. The design in these dresses is usually portraying a full representation of arms - most commonly with the arms of the husbands family juxtaposed with those of the wife’s own arms. Usually (but not always) the arms of the husband are seen of the right half on the dress, and the arms of the wife (inherited from her father) are seen on the left hand side of the dress. Should you be without a consort, you might consider including the arms of your household or even your Barony. The use of a four panel, cotehardie pattern will allow your replica to follow this model. Appliqué and couching techniques would work well in achieving these large bold design motifs. Other smaller or more intricate charges would best be worked in various embroidery techniques. To build up your design, use a ground fabric of your field colour and add the heraldic ordinaries and charges to the field fabric - this will best replicate the effect seen in these examples.

Sideless Surcotes

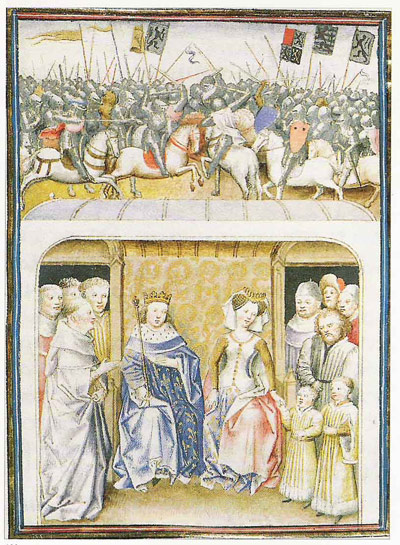

Heraldic sideless surcotes appear predominantly in miniatures from illuminated manuscripts and these depictions endured well into the 15th and 16th centuries - long after the sideless surcote stops being depicted as civilian dress. Many of these representations show women in this style of gown at formal and ceremonious occasions. The presence of crowns, denoting the royal status of the woman depicted, is evident in many of these examples. They appear primarily in continental manuscripts from the 13th century through to the 15th century.

|  |

|---|---|

| Figure 22 | Figure 22a (detail) |

(Voronova) Phillip, son of Louis IX, is crowned at Rheims. (1245-1285) (Plate188.F.261r)

Phillip III, (1245 to 1285), son of Louis IX, was married to Isabelle of Aragon until she died 1271, before marrying Mary of Brabant. The woman depicted in this illumination (Figure 22a) is likely to be Phillip’s second wife Mary, as the image in the top depicts the Dukes of Brabant and Luxembourg battling for Limbourg. Her ceremonial dress, bearing the fleur-de-lys heraldic motif, appears to be made out of the same fabric as Phillip’s robes, both garments denoting French royal status. This fabric was not just for individual identification, but was used to by members of French royal houses again and again in for an extended period of time - on sideless surcotes, bed hangings, horse covers, wall hangings, ceremonial robes, even on a dog coat! (Figures 23 to 27)

Figure 23

Horse covers - Isabella arrives in Paris.

Jean Froissart, Chroniques 15th C

Bibliotheque National de France, Paris

(BNF, FR 2643)

|  |

|---|---|

| Figure 24 | Figure 25 |

| Charles IV marries Marie de Luxembourg Grand Chroniques de France 1455-1460 | Coronation of Mary Brabant c.1530 Grand Chroniques de France 1455-1460 |

|  |

|---|---|

| Figure 26 | Figure 27 |

| Bed hangings and covers Charles VI Talking to Pierre Salmon 1412 Illumination Bibliothéque Publique et Universitaire, (Web Gallery Art) | (BL Online) Cloak/mantle Louis XII of France and Mary Tudor (sister to Henry VIII) Pagaent Palasi Royal - 1517 (British Library 6441 CottonVespian BII.f15) |

This reoccurring fabric, appears to have been used on clothing and soft furnishings, It was most likely woven, or the heraldic fleurs-de-lys embroidered upon a ground fabric. These heraldic fabrics would have been commissioned from textile manufacturers and embroiders guilds by royal households. We can support the existence of these types of heraldic fabrics by looking at the accounts of orders to the embroiderers guilds of the period, and a few extant examples.

From the accounts of the Paris Embroiderers Guild - ‘An order on 8 September 1352 to the armeurier au Roy et brodeur Nicholas Waquier for a horse-covering and room -hanging of velvet ornamented with fleurs-de-lis. The pieces were to be completed by All Saints day, and in that time 8544 embroidered fleurs-de-lis had to be produced and attached to the various items involved…. we find ’les fleurs de lis broudees jour et nuit en grant haste’, (fleur de lys embroidered day and night in great haste) and the embroiderers were aided in their work by the provision of candles and wine.’ (Staniland, pg30) These fabrics were most certainly created for ceremonial purposes.

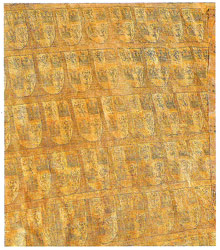

- Fig114 (no 8592 of 1863) woven silk tissue with the badges of Charles of Anjou, King of Sicily in 1266. gold coloured silk on a red ground castles are approx 2.5’ tall.

- Fig 115(no8252 of 1863) Italian 13th C. silk and gilt thread with a dark blue ground, fdl’s are 2’tall.

- Fig 116 (no 831 of 1863) Italian 13th C. the ground is dark blue and the crescents (3’ across) are gold. This pattern appears on the painted robes of Eleanor Queen of Henry II of England on her effigy in the Abbey of Fontevraud, Normandy.

- Fig 117 (no 49 of 1892) red and gold tissue of 13th Century

Above (Figure 28) is an artist’s representation (Houston pg 64) of some extant fabric fragments housed in the Victoria and Albert Museum’s textiles collection. (I am trying to source original photos of these to be included in this article but unfortunately they do not appear in the V&A’s Online Image Gallery). These fabrics are made from woven silk and originate from the middle of the 13th century.

The picture below (Figure 29) is an extant heraldic ‘pellote’ - a sideless surcote, from the collections of the Museo de Telas Medievales (Monasterio de Santa Maria de Huelgas, in Burgos, Spain). You will note it is made from the same half silk fabric that Don Fernando de la Cerda’s tunic (discussed earlier, Figure 8) is fashioned from. From this it may be reasonably assumed that the royal house of Leon and Castille commissioned a large quantity of fabric woven with this heraldic design (extant fabric Figure 9 and artist’s representation - Figure 30) from the Mudejar workshop in approximately 1270, with a view to putting it to multiple uses. This further supports the use of heraldic emblems and badges as design elements in fabric patterns, for use on heraldic secular clothing for men and women, but does not help us as evidence towards full garment armorial display.

|  |

|---|---|

| Figure 29 (Carretero) | Figure 30 (Monnas) |

| Pellote (women’s sideless surcoat) Monasterio de Santa Maria de Huelgas, in Burgos, Spain. | Fabric pattern and dimensions Ancient and Medieval Textiles. |

In this interesting image (Figure 31) we see the same strewn fleur-de-lys patterned fabric depicted on the dresses as discussed earlier. Strangely enough, the figure in the backgound seems to be wearing a heraldic houpelande which I’ve not seen elsewhere.

This figure is St Louis, to whom Jeanne of France and Blanche of Navarra are being presented. This picture is a 17th century reproduction done for Gaignieres - read totally unreliable (Lemoisne, Plate 12). I have been unable to unearth the original source for this image.

All the examples of sideless surcotes discussed thus far have used patterned fabrics of strewn heraldic charges on the skirts rather than full armorial displays. The only found exception to this appears in this image (Figure 32) of Isabella Stuart, Duchess of Brittany.

This picture is from The Hours of Isabella Stuart, which depicts Isabella before the Virgin and Child (Harthan pg 114). The majority of images discussed so far have been to commemorate, and indeed record, particular events or people. Where as this picture is a sacradotal image (patron or donor artwork), in which Isabella is deliberately depicted as pious and religious.

Whilst her armorial sideless surcote makes an excellent identification label, was it artistic license or did this dress actually exist? We readily accept information from other donor paintings as evidence of dress styles, even when lacking complete extant examples. Should the same consideration be applied here also? Though it is a rare example, it is my opinion that it is possible this heraldic dress may have existed as a ceremonial robe. These could have been commissioned by very wealthy royal women and worn as regalia.

Sideless Surcotes - Design And Construction Considerations

The use of heraldic sideless surcotes endured over many centuries, long after this style of dress ceased to appear in a fashionable context. These dresses are usually seen worn by royal women, and most certainly on the highest ranking lady in company. The use of these overdresses as ceremonial robes appears repeatedly. From these archetypal examples, similarities in design and construction emerge. The bodice on these garments appears to be predominantly white - made of, or trimmed in fur. Ermine furs appear with regularity. The skirt sections whilst, not usually having a full armorial display on them, often appear to have strewn charges on them quite commonly. The badges and motifs would be either woven into, or embroidered upon the fabric.

Should you be wishing to make one of these heraldic sideless surcotes, it would seem logical to construct your gown to reflect these design tendencies. That is, use fur on the bodice; and for the skirt, use an appropriately coloured field fabric with embroidered strewn charges/devices, rather than a full depiction of your device on your skirt. These overdresses are usually worn over close fitting single coloured cotehardie dresses.

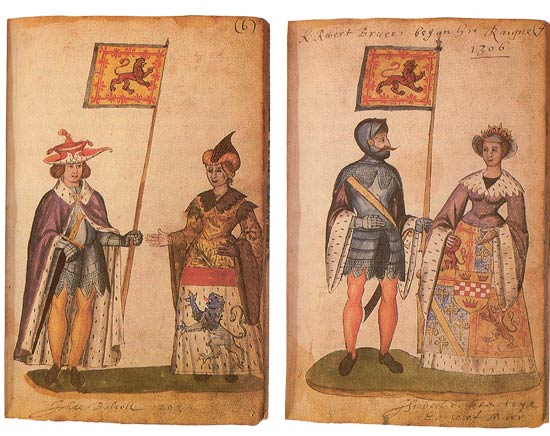

Tudor And Elizabethan Gowns

These late period dresses with heraldic foreparts occur only in armorial rolls - no supporting imagery from Tudor and Elizabethan paintings, extant garments of the period or written wardrobe accounts could be found. The existence of this type of heraldic women’s dress is highly unlikely, more so than the other styles discussed earlier.

|  |

|---|---|

| Figure 33 Joan Beaufort, and James I of Scotland Forman’s Roll, Scottish Manuscript 1563 | Figure 34 Mary Queen of Scots and Francis II of France, Forman’s Roll, Scottish Manuscript 1563 |

These dresses (Figures 33 and 34) are recognisable as being in the late Tudor, early Elizabethan style which is consistent with the fashion at the time when the Forman Roll was created. The Forman roll is named for it’s compiler, Sir Robert Forman, Lyon King of Arms who created it from 1555 to1563. In these examples, the foreparts of the skirts are emblazoned with heraldry - in both these cases, the arms are fully represented, but recontextualised to fit the triangular space of the forepart.

|  |

|---|---|

| Figure 35 Mary Queen of Scots and the Dauphin English manuscript The Seton Armorial 1591 | Figures 36 James III of Scots and Margaret of Denmark English Manuscript Hector Le Breton 16thC |

This image (Figure 35) depicting Mary Queen of Scots and her first husband, the Dauphin of France, appears in the Seton Armorial, an English manuscript of 1591. Due to the striking similarity of these two images, it would not be inconceivable that this image was fashioned on the previous one done in 1563 on the Forman Roll. The image depicting James III of Scotland and his Queen, Margaret of Denmark (Figure 36) it is ‘hardly a good likeness of the royal couple, but their heraldic garb renders them instantly recognizable’. (Williamson, pg18), which reinforces that these armorial roll are purpose designed for armorial identification.

John Balliol and his wife 1293 - Robert the Bruce and his wife 1306F

Figure 37 Balliol Armorial - English Manuscript c1330

Scottish National Library of Scotland (MS Acc9309)

And now for something completely different! These dresses are totally bizarre (Figure 37), having little or no resemblance to dress styles of Scotland in the early 14th century - the period this roll is dated from. Apart from being exemplary identification labels, they also illustrate lineage through the complex emblazonry. The hats worn by John Balliol and his wife don’t appear to reflect fashions of 13th /14th century Scotland either, which strengthens the idea that these dresses are fantastical. These gowns probably never existed. They are used here to denote important personages, illustrate their heraldry and nothing else.

Tudor/Elizabethan - Design And Construction Considerations

If you were wishing to create one of these later period style heraldic dresses, firstly, it should be remembered that evidence for them is less than substantial, and there is of course the chance they did not exist at all. Even though royalty are depicted in these manuscripts and we have established that the likelihood of royal women being garbed in heraldic clothing is greater than the likelihood of minor nobles being garbed so - Armorial rolls are designed to represent heraldry and not fashion. These manuscripts are not intended to be documentary for anything other than the heraldic data contained in them, so treat the costume information in them with scepticism. Should you still wish to make one, the examples found in the Seton and Forman armorials are probably the best models to follow. The construction of your dress would follow normal Elizabethan gown style and design. To make your heraldic forepart, use your entire device shaped into a triangular form as seen in the examples. The design could be applied using Elizabethan embroidery techniques in keeping with the style of the gown - various gold work methods, beading and silk embroidery.

Mantles/Cloaks

Like the heraldic sideless surcote, respresentatins of heraldic mantles appear to have endured the test of time. Perhaps this is due to their continued use as traditional ceremonial garments? We don’t know. Appearing in manuscripts from the 13th century through to brass monuments well into the 16th century, these cloaks could have been made predominantly for royal ceremonial occasions, and were unlikely to have been worn in a fashionable, everyday context.

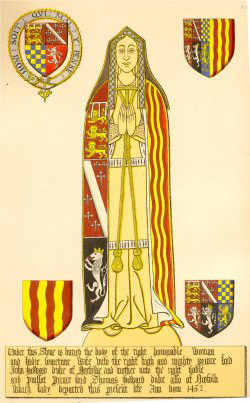

Figure 38 and 39 Lady Katherine Howard

Brass engraving, Stoke-by-Nayland, Suffolk, c. 1535.

Drawing by John Sell Cotman

Lady Katherine Howard, fifth wife of Henry VIII of England, met a miserable end. Here is the brass rubbing (Figure 38) and an artist’s representation (Figure 39) of her funereal monument, where she appears in a heraldic mantle. The artist has taken quite a few liberties with the design, even altering the arms on her mantle. This could certainly be representative of a royal ceremonial cloak. Though I have not found any wardrobe accounts to support it’s existence, it serves to visually depict Katherine Howard’s claims to nobility - reinforcing her worthiness as consort to the King when many considered her unsuitable. This intricate mantle, appears to incude the arms of England, Howard, Warrene (Surrey), Mowbray and others.

|  |

|---|---|

| Figure 40 (MBS) Joice Tiptoft Brass funeral effigy 1446, Enfield, Middlesex | Figure 41 Joice Tiptoft depicted attending on HRH Margaret Princess of Wales c1400s (Victorian painting) Falko von der Weser |

Joice Tiptoft (daughter of Eleanor, widow of Roger Mortimer Earl of March, and herself widow of John Baron Tiptoft), is depicted here (Figure 40) in a heraldic mantle worn over a sideless surcote of ermine bodice and plain skirt. The artists representation of Joice (Figure 41)appears to be a Victorian painting of her based on the brass effigy. Oddly, Joice’s mantle doesn’t appear to bear the arms of Tiptoft.

Figures 42 (Norris) and 43 (Clayton)

Elizabeth, Countess of Oxford,

2nd wife of Willliam, Viscount Beaumont 13th Earl of Oxford

Wivenhoe Church, English Brass c.1537

|  |

|---|---|

| Scrope | Tiptoft |

These two images derive from the 1537 funereal brass monument depicting Lady Elizabeth Scrope, Countess of Oxford. The sideless surcote depicted on Lady Elizabeth, appeared to be made of a white fabric with embroidered heraldic ermine motifs on it. Her heraldic mantle, displays the arms of Scrope, ‘Azure, a bend Or’ quartered with Tiptoft ‘Argent, a saltire engrailed, Gules’ which are the historically correct arms for these eminent families.

The first image (Figure 42) is a drawing of the original brass effigy (Norris). As you can see from a rubbing of the original monument (Figure 43), the artist has taken extraordinary liberties with his representation, which is very disappointing

Jane Guildeford, Duchess of Nothumberland (Figure 44) is also depticted on her funereal monument wearing an heraldic mantle. This cloak has far more intricate marshalling, depicting the arms of Guydeford, Halden, West, La Warr, Cantelupe, Mortimer and Grelle. (Norris pg?).

This drawing also needs to be compared to the original brass, which I am still trying to source. Looking only at the drawing, I would imagine the artist has made quite a few changes. This drawing depicts the kneeling woman in a very broard triangular arrangement, whereas figures shown kneeling in brass monuments typically appear more elongated. Should anyone be in the vicinity of St Luke’s Church, Chelsea, I would love a picture of the original!

Figure 44 (Norris)

Jane, Duchess of Northumberland, Sister to Sir Henry Guyldeford, Married to John Dudley

St Luke’s Church, Chelsea, English brass c.1555

Figure 45

Anne Neville, Queen to Richard III 1456-1485

Salisbury Roll (15thC English Manuscript)

This intricately emblazoned mantle shown here worn by Anne Neville, Queen consort of Richard III of England. (Figure 45). The illustration comes from the Salisbury Armorial Roll, (15th century). Anne is depicted here in a royal ceremonial mantle, which given her royal status may have been made for stately occasions. The elaborate design serves to emphasise her suitability as royal consort by visually establishing lineage.

The ermine depicted at the top of this mantle is not intended to be included as part of the heraldic information, but should be considered a depiction of an ermine shoulder cape, fashionable in cloak design from the 14th century onwards.

Figure 46 (MBS)

Sir William Catesby and Margaret Scrope.

Brass funeral effigy c.1485

Ashby St Leger, Northhamptonshire England

Sir William Catesby and his wife Margaret Scrope (daughter of Lord John Scrope of Bolton)are depicted in this brass monument (Figure 46). In this interesting image we see Sir William wearing a heraldic surcoat which he no doubt could have possessed, and his wife us adorned in an elaborate heraldic mantle. We can tell immediately that these garments are not solely intended to identify the wearer, as their heraldry is already apparent elsewhere on the monument. The inclusion of the heraldic clothing is superfluous in this instance. Perhaps the reason for including these heraldic garments is due to it’s actual existence in this case.

The figure below, (Figure 47) shows Sir Richard Fitzlewes wearing a heraldic tabard. Pictured with Sir Richard are his four wives, all but one of whom are wearing heraldic mantles. Sir Richard died in 1528, at the great age of about 82, having survived all his brothers and even his own sons. His heir was his grand-daughter by his eldest son John Fitzlewes, Ella, wife of John Mordaunt.

Despite having many wives and offspring, the name of FitzLewes died with him. Perhaps this was why he chose such an elaborate brass monument with such a grandiose display of heraldry to memorialise the Fitzlewes name.

Figure 47 (MBS)

Sir Richard Fitzlewes, English Brass Ingrave, Essex 1528

Mantles/Cloaks - Design And Construction Considerations

These mantles are highly reminiscent of period heralds tabards with their complex quarterings. If they existed they would most likely have been constructed using similar techniques - a mixture of appliquß, couching, gold work, and silk embroidery. These cloaks, worked with sophisticated and intricate embroidery would have been particular cumbersome and heavy. None of the examples discussed appear to be fur lined, perhaps this would have been a concession to their already unwieldy weight.

In the SCA we do not subscribe a system of inherited arms and the use of marital marshalling implying hereditary lineage of arms is discouraged. Should you wish to mirror the intricate quarterings, you might consider including the arms of your consort, household or barony, as marks of affiliation rather than as a display of inherited arms. It is unsure what your cloak should look like from behind, but none of them appear to be overly full in cut. Using a cloak pattern that isn’t particularly full would allow the heraldry to appear flatter and more easily discernable when worn. As the cut of the cloak becomes fuller, more of the heraldic design will fall into the folds of the cloak rendering it less recognisable. And Finally…

So, after much wailing and gnashing of teeth, we conclude by recognising that the resources currently available on this ambiguous subject are not concrete enough to definitively prove the existence of women’s heraldic frocks in a fashionable context for the 1066AD to 1600AD period. Extant garments, textile fragments and written accounts support the use of heraldic adornment on womens clothing, particularly the repeated use of strewn badges. But I have yet to find any reliable sources to support the use of full garment representations of personal arms on womens clothing. While this is the case, it is my personal opinion that it is a sweeping generalisation to state that these heraldic dresses did not exist at all. It would be far more accurate to say that certain styles are more likely than others, and their use would have been exceptionally specific. (Netherton)

I believe that heraldic sideless surcotes could possibly have existed, and if so, they would have been worn as ceremonial ‘costumes’ by royal women for official state occasions and not as clothing as such.. It is also my opinion that heraldic cotehardies and mantles could be considered possible, but not probable. The concept of minor noble women wearing such elaborate garments could be a display of pretension rather than accurate representation, and it seems highly unlike that minor nobles would have had owned such elaborate heraldic ceremonial costumes. I am totally convinced that the Tudor/Elizabethan style gowns is fantastical, and consider them extremely unlikely, largely because the only sources I have found on these are not intended to document anything other than heraldry.

In the arena of modern medieval re-enactment, heraldic display of all kinds greatly enhances the atmosphere we are attempting to recreate, and our experience therein. In the SCA in particular, we aim to recreate the niceties of the Middle Ages and are often prepared to make many concessions to authenticity in our game for the safety, hygiene and the enjoyment of all. After years of procrastination, (and knowing it may be many more years before this conundrum is definitively solved), it is my opinion that if making and wearing heraldic gowns is going to increase your enjoyment of these modern Medieval times - then make several!

Bibliography

- Bartlett, Robert Medieval Panorama

Thames & Hudson Ltd, London 2001

ISBN - 0892366427 - Cantor, Norman F - The Pimlico Encyclopaedia of the Middle Ages

Random House, London, UK 1999

ISBN 0892366427 - Carretero, Concha

H Museo de Telas Medievales

Monasterio de Santa Maria la Real de Huelgas

Patrimonio Nacional, Spain 1988

ISBN - 8471201275 - Clayton, Muriel Brass Rubbings.

Cat.of Rubbings of Brasses & Incised Slabs.

V&A Museum HMSO, London

ISBN 0112900879 - Coss, Peter - The Lady in Medieval England 1000-1500

Sutton Publishing, Gloucestershire 1998

ISBN 0905778367 - Evans, Joan Flowering of the Middle Ages

Thames & Hudson London, 1985

ISBN 0500280436 - Hallam, Elizabeth - Chronicles of the Age of Chivalry

Crescent Books, England, 1995

ISBN 0517140802 - Holme, Bryan - Medieval Pageant

Thames & Hudson, London 1987

ISBN 0500014213 - Jacquemin, R.A Iconographie Generale et

Methodique du Costume du IVe au XIXe Siecle - John Harthan Books of Hours and Their Owners

Thames & Hudson, London, 1977

ISBN 0500232172 - Houston, Mary G Medieval Costume in England and France

The 13th, 14th and 15th Centuries

Dover Publications Inc., New York 1996

ISBN 0486290603 - Lemoisne, P.A Gothic Paining in France - 14th and 15th C.

Hacker Art Books , New York, 1973

ASIN 0878170758 - Marks & Payne British Heraldry from it’s Origins to c.1800

British Museum Publishing Ltd 1978

ISBN 0714100854 - Monnas, Ancient and Medieval Textiles

Studies in honour of Donald King

W.S. Maney & Sons Ltd, Leeds

ISBN 0903859157 - Norris, Herbert Tudor Costume and Fashion

Dover Publications Inc., New York 1997

ISBN 0486298450 - Staniland, Kay - Embroiderers - Medieval Craftsmen Series

University of Toronto Press, 1991, Toronto

ISBN 0802069150 - Williamson, David Debrett’s Guide to Heraldry and Regalia

Headline Book Publishing, London, 1992

ISBN 0747206090 - Voronova, Sterligov Western European Illuminated Manuscripts

Parkstone Press, United Kingdom 1996

ISBN 1859952402

Web References

- Asmolean Museum

- Bibliotheque Nationale du Paris

- British Library Online

- National Portrait Gallery UK

- New York Public Library Online Picture Catalogue

- Pierpoint Morgan Library’s Corsair

- Scottish National Library

- DScriptorium

- Victoria and Albert Museum Online Image Gallery

- Web Gallery of Art

Quite a few people have generously shared their resources, and I wish to thank them for their input…

- Carolyn Fraser (Mistress Eleanor of Orkney)

for giving me access to her library - Steve Roylance (Master Thorfinn etc)

for info from ‘Books of Hours and Their Owners’ - Dominic Hunter (Master Wolfgang Adolphus Jäger) from Drachenwald,

for info on some Brass rubbings - Jan Tonnesen, Wahrenbrock’s Book House, San Diego, California

for info from ‘Gothic Painting in France’ - Toni Cross (Lady Salaberge de Granson)

for proof reading this overgrown set of notes - Ken Karmiole, Karm Books, Santa Monica, California

for information from Jacquemin’s ‘Iconographie’ - Robert Hutchinson, Grantly’s Books, Sherborne; United Kingdom

for info from ‘A Mirror on Chaucer’s World’ - and especially Robin Netherton

for discussions via email, and for promising us a publication on this subject!